Five Key Facts On Controversial Researcher’s Latest Attempt to Link Fracking to Health Impacts

A new study from University of Colorado School of Public Health professor Lisa McKenzie purports to show a link between living in proximity to oil and natural gas production with congenital heart defects. But like her 2014 study on such defects and other previous research, McKenzie’s latest epidemiological study is riddled with limitations and inconclusive findings.

This study marks the latest iteration of the McKenzie playbook cycle we’ve seen repeated time and again since 2012. A quick recap of each study roll-out goes as follows:

- A press release announcing the study generates media interest and alarmist headlines.

- These headlines overstating the connection between energy development and health impacts are seized upon and promoted by activists.

- Later on, Colorado state regulators respond to the study explaining its limitations after the narrative has been spread.

There are a few factors in her latest study that show McKenzie and her team are up to the same tricks. Here are five important facts to keep in mind when reading it:

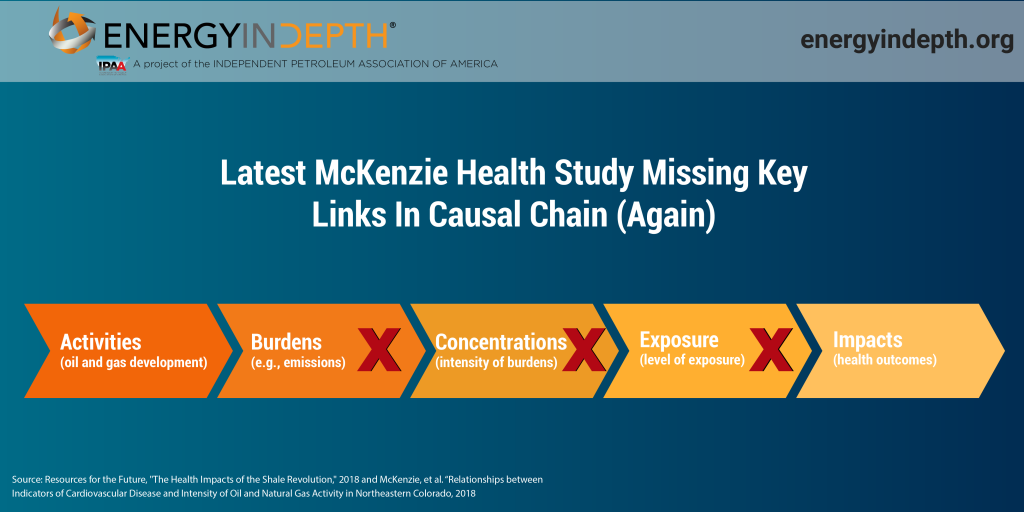

FACT 1: Researchers Did Not Take Any Actual Air Measurements

As is the case in most of the epidemiological research analyzing potential health impacts of oil and natural gas development, McKenzie did not measure any emissions for this study.

Instead, the researchers simply lined up data from various sources to estimate what they think exposure intensity would have been.

The databases only measured locations of oil and natural gas production in relation to the subjects’ residences, but this leaves significant room for error without sampling. In fact, the study that McKenzie uses to create her own estimates lists several limitations to its research:

“There are missing dates for when drilling (28%) and hydraulic fracturing and flowback (43%) occurred.”

“Emissions data used in this analysis were collected from 2013 to 2016 and from well pads that were using current practices for drilling and hydraulic fracturing and flowback. … [U]sing these emissions data might over or underestimate past emissions.”

“Another limitation of using the emissions studies is that we did not have access to all site-specific information, including location…”

McKenzie and her team also claim to account for emissions from non-oil and natural gas sources, but in reality all that means is they accessed a public EPA database and entered those amounts into their models. From the study:

“Similarly, accounting for the density of other O&G facilities and intensity of air pollution sources not associated with O&G activities is an improvement on previous studies, but limitations remain. Small scale fixed air pollution sources, such as gasoline stations, and mobile air pollution sources were not included in our analysis. This may be obscuring our ability to observe associations in urban areas, such as Greeley CO, where these air pollution sources are more prevalent than in rural areas.” (emphasis added)

Further, this study relies on emissions and birth data collected between 2005 and 2011. Most of the information is more than a decade old and does not include regulatory changes or technological advances made since 2011. In particular, it does not account for Colorado’s 2014 rulemaking that made the state’s oil and natural gas regulations among the “strictest” in the country and instituted the nation’s first limit on methane from oil and natural gas wells.

In other words, McKenzie and her team make a lot of assumptions to reach their conclusions, even while arguing that this study is more robust than previous versions, and do not take into account important strides in emissions reductions that have occurred.

FACT 2: Birth Certificates Only Provide A Snapshot of Information On Mothers

While McKenzie claims this latest study is an attempt to address limitations of her similar 2014 study by carrying out a “more robust evaluation of the relationship” between oil and natural gas activity and congenital heart disease (CHD) births, there are still a substantial amount of shortcomings in the research.

For instance, the researchers rely on birth certificates for maternal data, but do not have access to the health history of the mother.

“Data on covariates were limited to information on the birth certificates and thus we were not able to adjust for maternal health and nutrition that may have resulted in residual confounding of unknown bias.”

As the Magee-Womens Research Institute and Foundation explained when criticizing another study that used birth certificates to draw conclusions about fracking:

“Birth certificates do not record every pregnancy outcome. Therefore the researchers were able to evaluate only a limited number of outcomes…” (emphasis added)

The Center for Disease Control lists smoking, obesity and diabetes as leading causes of increased risk for CHDs, but the McKenzie study only accounts for smoking in its findings. And even then, pregnant mothers must self-report smoking to doctors for it to be included in their child’s birth certificate.

How many of the mothers included in the study had additional risk factors for CHDs?

FACT 3: Regulators Have Been Highly Critical of McKenzie’s Previous Work

McKenzie’s previous work has come under heavy scrutiny from fellow researchers and government agencies for attempting to make links to oil and natural gas production with poor health outcomes based on flawed or incomplete data. In fact, Colorado’s top health regulators have reviewed many of Lisa McKenzie’s previous studies and found significant limitations, even referring to her conclusions as “misleading.”

In this study, McKenzie cites her own similar 2014 research where she claimed an examination of 124,842 births in rural Colorado from 1996 to 2009 “found that CHDs increased with increasing density of oil and gas wells around the maternal residence.”

But Dr. Larry Wolk, then the executive director of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment immediately refuted McKenzie’s 2014 work, which relied on data from his agency.

“As Chief Medical Officer, I would tell pregnant women and mothers who live, or who at-the-time-of-their-pregnancy lived, in proximity to a gas well not to rely on this study as an explanation of why one of their children might have had a birth defect. Many factors known to contribute to birth defects were ignored in this study.” (emphasis added)

A few months later, CDPHE completed its own investigation of 22 reported anomalies in unborn children, which looked at more than a dozen potential factors – including proximity to oil and natural gas wells. The agency concluded:

“Our investigation looked at each reported case and concluded they are not linked to any common risk factors.”

FACT 4: McKenzie Mischaracterizes Existing Research In Her Analysis

McKenzie cites a recent study of birth defects in Oklahoma that she claims, “found positive but imprecise associations between proximity to oil and gas wells and several types of CHDs.”

A check of that study however reveals that the researchers didn’t actually examine oil and natural gas wells. The Oklahoma study actually looked at the association between birth defects and benzene, a common chemical also found in motor vehicle exhaust, gas stations, and auto repair stations. In fact, at the end of the study, the researchers say they plan to examine oil and natural gas production separately because they had not done so in their study.

Importantly, the Oklahoma study’s conclusions actually undercut McKenzie’s claims:

“We observed no association between benzene exposure and oral clefts, CCHDs or NTDs. … Our findings do not provide support for an increased prevalence of anomalies in areas more highly exposed to benzene.” (emphasis added)

FACT 5: Colorado Health Regulators’ Data Shows No Link to Health Impacts

As EID has previously shown, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has studied the potential health impacts of oil and natural gas development closely and its findings are contradictory to McKenzie’s research.

CDPHE’s most recent health study reviewed more than 10,000 air samples in areas of the state with ‘substantial’ oil and gas operations, and found emissions levels to be “‘safe,’ even for sensitive populations.”

Conclusions

As Dan Haley, president of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, pointed out, McKenzie’s latest study looks to just be a rehash of her previous work:

“This study is not new. It’s a reexamination of her 2014 report using the same old data from 2005 to 2011 — data that has no relevance to current regulations or to the common practices used by today’s operators. Interestingly, this study says particulate matter from oil and gas operations could lead to these health effects, but that contradicts the conclusions of another McKenzie study published just last month that found particulate matter levels near Colorado oil and gas operations were three times lower than EPA national air standards. Bottom line, the data is old and no air samples were taken. However, air samples that have been taken by Colorado’s health department, for many years now, are conclusive. After thousands of thousands of air samples, many of which have been collected near oil and gas operations, not one exceeds state or federal protective health guidelines. Dr. McKenzie’s studies have been called “misleading” in the past, and this seems to be par for the course.”

And of course, it wouldn’t be a McKenzie study if its main conclusion wasn’t the need for more research, which we see here:

“Taken together, our results and expanding development of O&G well sites underscore the importance of continuing to conduct comprehensive and rigorous research on the health consequences of early life exposures to O&G activities.”

This latest report will most likely garner headlines across the state, but as we’ve seen before, her work requires a little more scrutiny before jumping to conclusions.