Controversial Colorado Researcher Dubiously Links Fracking to Health Impacts

University of Colorado Public Health professor Lisa McKenzie’s latest attempt to connect oil and natural gas development to health risks – this time involving precursors to cardiovascular disease – produces the same results as her team’s previous research: a failure to actually link fracking to these issues despite what media reported.

The key finding from this latest McKenzie et al. study is a “possible connection” that volunteer participants who lived near higher “intensity” oil and gas operations had increased levels of pre-indicators of cardiovascular disease. They also conclude that more “robust” research is needed – which appears to be Prof. McKenzie’s M.O. (which we will address in a minute).

How they reached such a conclusion with even a loose correlation, given the scope of limitations acknowledged in the report, is a bit of a mystery. Here are five key things to know about this study.

#1. Researchers failed to measure air and noise pollution.

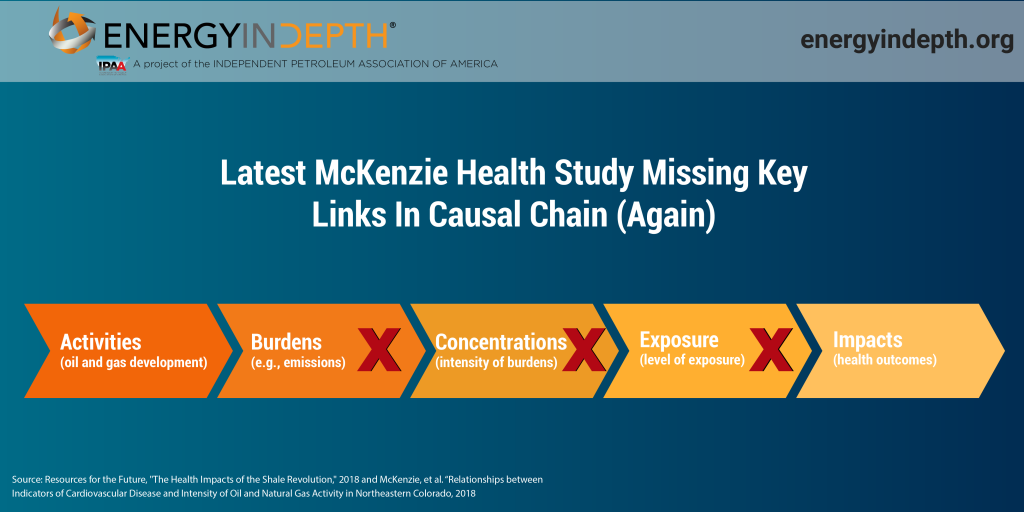

Environmental think tank Resources for the Future recently detailed a five-step “impact pathway” that researchers should use to “measure each link in the causal chain that could potentially lead to health impacts from oil and gas development…” Instead, these researchers jumped from activities – individuals lived in close proximity to oil and natural gas development – to health impacts – individuals experienced indicators of cardiovascular disease – without ever measuring for any air and noise pollution (burdens), the intensity of those emissions in relation to the residence (concentrations) or the level of exposure people actually experienced.

Notably, the researchers admit that this is a key limitation of their study:

“Because we did not directly measure exposure to noise and air pollution, our study was not able to elucidate possible mechanisms or environmental stressors that might be involved.” (emphasis added)

Read: Because McKenzie et al. failed to take measurements, they can’t actually determine what’s causing these cardiovascular issues or if oil and natural gas development was indeed a factor at all. In fact, any associations that were found could actually have been simply a coincidence, as the report further explains that,

“[B]ecause we conducted numerous statistical tests, we recognize that we could observe statistically significant associations by chance.” (emphasis added)

How something could be both “statistically significant” and also a coincidence is a bit of a conundrum.

#2. The sample size for this study was incredibly small and unrepresentative of the general population.

McKenzie et al. also acknowledges that,

“Additionally, limitations in our exposure estimate and sample size prevent us from evaluating dose-response effects.”

According to the report, “The participants in the low exposure tertile resided exclusively in Fort Collins, while those in the high exposure tertile resided in Greeley or Windsor.” Those three municipalities represent a population of just under 296,000 people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The 97 volunteers who were evaluated in the study represent less than one half of one percent of the population, at 0.03 percent. Not only is the sample size an insignificant representation of the population, but McKenzie et al. explain that the participants, “may be different from nonparticipants in many ways, so our results may not be applicable to the general population.”

As the report further explains,

“Participants in the high exposure tertile were older and less educated than participants in the other tertiles. Participants in the low exposure tertile had lower incomes and were more likely to be working part-time than participants in the other tertiles.” (emphasis added)

Translation: Participants living closest to more intense oil and natural gas activity represent a category of people that are traditionally more likely to experience symptoms of cardiovascular disease. As the Center for Disease Control explains, “Your risk for heart disease increases as you get older.”

#3. Study participants had potential precursors, not actual diagnoses of cardiovascular disease, that were inconsistent with the intensity of nearby oil and natural gas development.

McKenzie et al. found that the volunteers in the study had “important markers of cardiovascular health and the observed responses in our population are in the range that have been associated with increased risk of [cardiovascular disease].” But according to the researchers, these precursor symptoms were not consistent across the determined ranges of oil and natural gas development, and as such “warrant caution in interpretation.” In fact, concentrations of certain markers in the “medium exposure” group were lower than in the “low exposure” group.

“While IL-1β and TNF-α plasma concentrations also were highest in participants living in areas with the greatest O&G activity, wide confidence intervals that include zero warrant caution in interpretation. In this population, we did not observe an association between IL-6 and IL-8 plasma concentrations and intensity of O&G activity.” (emphasis added)

If there was a direct causal relationship, the medium exposure group where oil and gas activity was more intense should not have seen lower plasma concentrations than the low exposure group, and associations should exist consistently.

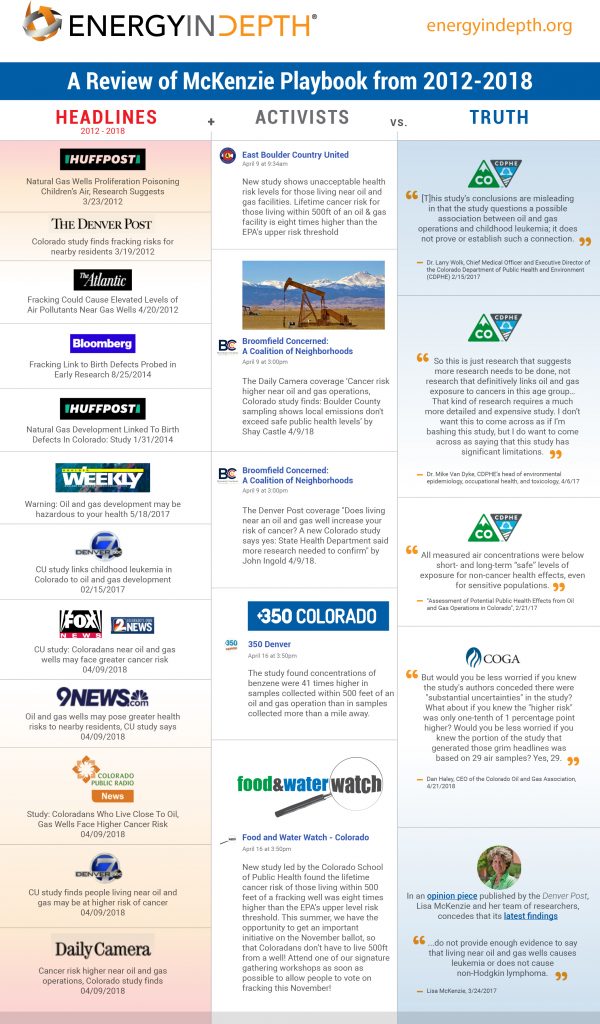

#4 McKenzie et al. have been criticized for similar research limitations on numerous occasions.

This team’s series of studies on fracking and health have been highly criticized. Most notably the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has continuously disavowed their research:

- McKenzie et al. claim: “[L]ifetime cancer risk of those living within 500 feet of a well was eight times higher than the EPA’s upper level risk threshold.”

- CDPHE response: “This study confirms our 2017 findings of low risk for cancer and non-cancer health effects at distances 500 feet and greater.”

- McKenzie et al. claim: “[A]cute lymphocytic leukemia” are more likely to live within 16.1 kilometers – that’s 10 miles – of an oil and gas well.

- CDPHE response: “[T]his study’s conclusions are misleading in that the study questions a possible association between oil and gas operations and childhood leukemia; it does not prove or establish such a connection.”

- McKenzie et al. claim: There is an association between birth defects and oil and gas development.

- CDPHE response: “[W]e disagree with many of the specific associations with the occurrence of birth defects noted within the study. Therefore, a reader of the study could easily be misled to become overly concerned.”

Resources for the Future also took a hard look at previous McKenzie et al. studies in its comprehensive 2017 report on health studies related to fracking. The environmental think tank found numerous problems.

#5 This is just the latest in a string of reports by McKenzie et al. that follow a set playbook for pushing flawed research through media and activist channels.

This is not the first or even the third time we’ve seen Prof. McKenzie release a study based on loose correlations (assumptions) that results in generating misleading headlines. This cycle is set on repeat and the same result is always observed:

- Step 1: Report is released that carries with it an over-generalized conclusion and is accompanied by an alarmist headline.

- Step 2: State regulators face inquiries and push back against the studies, pointing out their limitations and clarifying what the findings actually conclude.

- Step 3: Nonetheless, media report on each study with varying levels of scrutiny.

- Step 4: Activists seize the headlines to spread anti-fracking sentiment and scare the public.

Conclusion

Heart disease is the No. 1 cause of death in the United States and about 47 percent of Americans have at least one of the three precursors for it, according to the CDC. Given these statistics, it’s not surprising that people living near oil and natural gas development – or any development for that matter – would also be considered at risk for it, especially older people.

Prof. McKenzie’s attempts to use data points to achieve her desired outcome – i.e. misleading the public over a correlation between health ailments and oil and gas development where no evidence of causation exists – do not move the needle on studying potential health risks. So, don’t be fooled by the headlines, this study is no different than all of her others.