Harvard Study on Early Deaths Lacks Critical Data

A new study from Harvard University that dubiously claims to link unconventional oil and natural gas development with the premature death of Medicare beneficiaries is deeply misleading and flawed in its assumptions, data and approach.

In a press release touting the study, the researchers write:

“The results suggest that airborne contaminants emitted by [unconventional oil and gas development] and transported downwind are contributing to increased mortality.”

Fact check: It doesn’t.

In reality, this study simply compares the location of wells completed between 2001 and 2015 to the population of elderly residents in a certain zip code. Correlation doesn’t equal causation and it couldn’t be truer in this case, where no air samples were taken, measurements conducted, or exposure pathways established.

Here’s are some important things to keep in mind when reading this study:

#1 Living in the same zip code as a well does not mean that a person lives next to a well.

In identifying their own limitations to the study, the researchers wrote:

“Third, we had available data on the ZIP-code level but not on the street-level address of residence. This could result in potential exposure misclassification; however, we used a population-weighted method to mitigate this issue.” (emphasis added)

This is hardly a minor limitation and is arguably the most glaring issue with the study.

To state the obvious: there is a massive difference between a specific address of a resident and the zip code.

In densely populated cities and suburbs – say Philadelphia, Harrisburg or Pittsburgh – there are many zip codes that break up the city by different Post Office locations. In other words, the city itself may encompass a large land area, but the individual zip codes break that up into smaller, more concentrated segments.

But in rural communities where unconventional development is more likely to occur, that’s not usually the case. In fact, one postal zip code can include several townships spread 20 or even 100-square miles.

This means that residents might be in the same zip code as a well, but their actual address could be many miles from the site location. Yet the researchers don’t take this into account and instead, inaccurately assume that every person in a zip code lives “close” to a well.

#2 The researchers did not take emissions measurements for exposure and concentration.

Regardless of proximity to the actual well location, it doesn’t change the fact that proximity is not a suitable proxy for exposure. What does that mean?

The researchers never took any actual measurements at oil and natural gas production sites. Instead, they established an undefined area around each well and assumed that anyone downwind of that well – or in that zip code – could potentially be affected.

They write:

“Previous studies also did not investigate the exposure pathway(s) through which UOGD activities could lead to adverse health effects, primarily due to the lack of any large-scale measurement of UOGD-sourced pollutants in some intensively drilled regions. To address these gaps in the data and characterize the spatiotemporal gradients of the UOGD-sourced agents, investigators have designed proximity-based exposure (PE) metrics of varying complexity.”

They explain further in their limitations:

“First, we were unable to estimate the associations between specific UOGD-related airborne agent(s) and mortality due to the unavailability of high-resolution exposure data of air pollutants other than PM2.5. Therefore, our results should be cautiously interpreted as the mortality risk associated with an air-pollutant mix that originates from UOGD wells.”

While the study attributes this substantial shortcoming to a lack of available data, the reality is that studies have shown that emissions from well sites are below levels that would impact health. In fact, a 2019 study that used stationary air monitors to monitor emissions of fine particulates, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone and benzene between 2011 and 2015, found:

“The implication of these results was that using this methodology in epidemiology studies can result in significant exposure misclassification and therefore, uncertainty around reported risk estimates… Further study including disease outcomes and exposure classification of cases and controls would be needed to fully understand the nature and degree of the misclassification.”

The 2019 study further explained:

“The question we essentially asked was, if [Pennsylvania] monitoring sites were instead a sample of epidemiology study subjects’ homes with monitors placed outside the front door, how well does the categorization of exposure agree between the two methods? We found that they did not agree well at all with the same exposure quartile assigned in roughly one in four observations, and the opposite category assigned for roughly 25%.” (emphasis added)

#3 Researchers studied the elderly population without accounting for existing health conditions.

The study focused on the effects of oil and natural gas production on the elderly (Medicare beneficiaries) but lacked several key acknowledgements. Ashe researchers explain:

“Mortality data. Our study area (Fig. 2) includes all Medicare beneficiaries who live in ZIP codes within or around seven major shales defined by the US Energy Information Administration. The Medicare beneficiaries denominator file was obtained from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service31. We grouped the ZIP codes into three non-adjacent subregions: northern, eastern and southern, and then built an open cohort with person-years of follow-up for Medicare beneficiaries who were 65 years or older at enrollment who lived in a ZIP code included in the study area for at least one year from 2001 to 2015. For each person-year of follow-up, we extracted individual data on age, race, sex, Medicaid eligibility, place of residence within the ZIP code and date of death.”

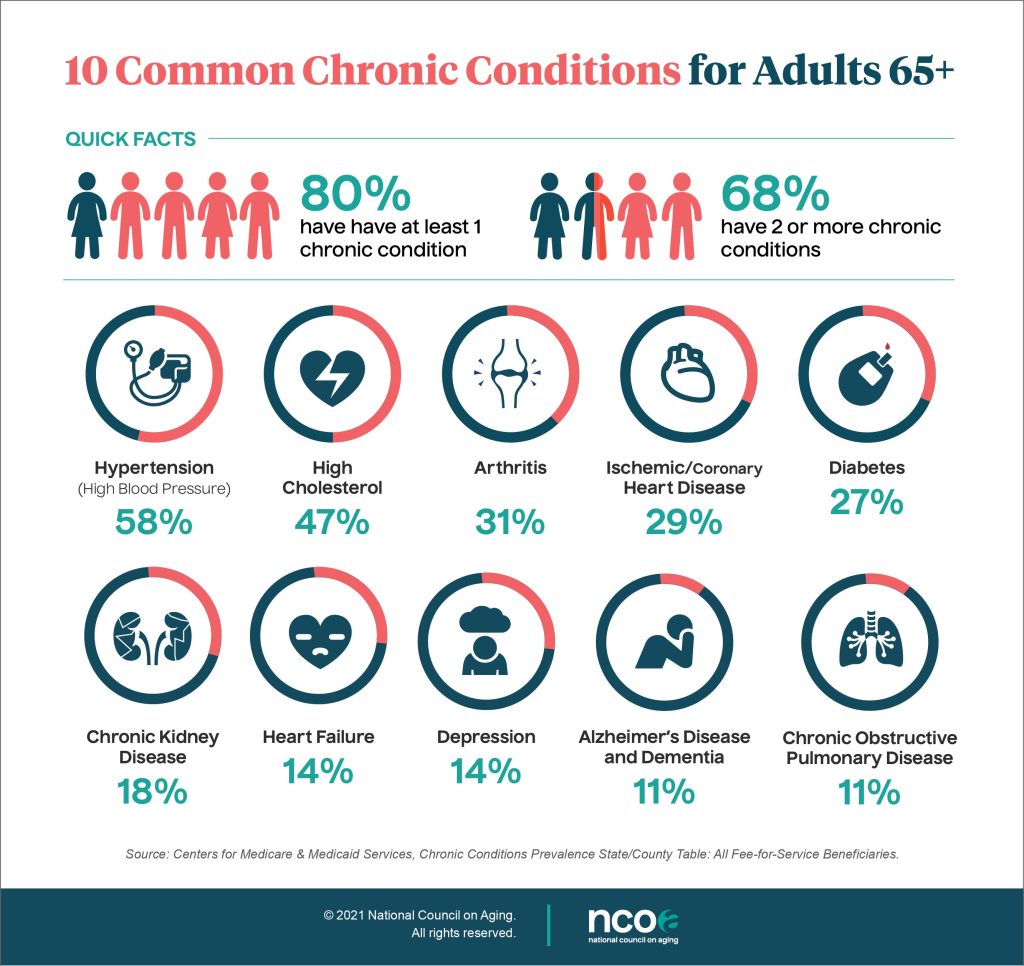

Notably absent from the list of covariates is existing health issues. While being elderly does not always mean a person has a major health concern, statistically there’s a high likelihood. According to the National Council On Aging:

“Eighty percent of adults 65 and older have at least one condition, while 68 percent have two or more.”

All of these conditions – most commonly including things like high blood pressure and cholesterol to diabetes and heart, lung or kidney disease – can impact the longevity of a person’s life. And yet none of these were included as potential causes of death within the study.

Source: National Council On Aging

Notably, research commissioned by Energy In Depth in 2017 that looked at morbidity rates in Pennsylvania counties with the highest number of wells from 2000 to 2014 – the Harvard study analyzed 2001 to 2015 – found:

“There was no identifiable impact on death rates in the six counties attributable to the introduction of unconventional oil and gas development. In fact, the top Marcellus counties experienced declines in mortality rates in most of the indices.”

Further, in relation to the elderly population in particular:

“The proportion of elderly-to-total population increased significantly in the top Marcellus counties compared to the state. Based on this fact, death rates in these six counties would be expected to increase, but this expected increase did not occur.” (emphasis added)

In regard to chronic lower respiratory disease that could be exacerbated by the assumption made in the Harvard study of increased PM 2.5 from wells within a zip code, the EID-commissioned research found:

“Unconventional gas development was not associated with an increase in deaths related to chronic lower respiratory disease (including asthma) in the top Marcellus counties, as the overall chronic lower respiratory disease mortality rate declined (improved) or was variable for the six-county area. The only exception was Greene County where the increased mortality rate was consistent with the increase in the elderly population.” (emphasis added)

#4 At least one author was part of a flawed study on PM2.5 and Covid-19.

One of the study’s authors, Francesca Dominici, a biostatics professor at Harvard, was also the author a flawed study from 2020 that attempted to link PM2.5 to increased risk of death from COVID-19.

As EID Health pointed out at the time, that study wasn’t peer-reviewed before it was published and came under withering criticism from other scientists for using a deeply flawed methodology like a failure to assess for individual considerations for those who succumbed to the disease. As epidemiologists Paul Villeneuve and Mark Goldberg wrote:

“[Ecological] studies do not use data at an individual level. They are not highly regarded in epidemiology because they have many limitations that prevent them from providing insight on cause-and-effect relationships. This study is no different. … “In the study, each county was associated with one value of air pollution. But a county can be so different from another in terms of size and population, it makes little sense to do so.”

Conclusion

The natural gas and oil industry absolutely supports, encourages and advances sound, credible scientific research. Unfortunately, this latest study makes major assumptions without the evidence to back it up, resulting in claims that are far from reality.

It’s telling that the study was supported by grants from the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institute of Health and Harvard University, but none of those organizations actually endorse the findings of the research:

“Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the US EPA, NIH, or Harvard University.”