Anti-Fracking Donor Memo Mapped Out Strategy to Attack Oil and Gas with Questionable Health Claims

A strategy memo from 2012 encouraged anti-fracking groups to make connections between health problems and fracking, even when no evidence existed to support the linkage. The goal of the plan, which included leveraging the power of the media and a focus on young children, was to undermine support for oil and natural gas development and expand regulations.

The 2012 memo, entitled “Public Health Dimensions of Horizontal Hydraulic Fracturing: Knowledge, Obstacles, Tactics, and Opportunities,” was authored by Seth Shonkoff, who at the time was a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. Shonkoff is now the executive director of an Ithaca, N.Y.-based group called Physicians Scientists & Engineers for Healthy Energy (PSEHE), which describes itself as “a multidisciplinary research and policy institute focused on the adoption of evidence-based energy policy.”

An Energy In Depth review of documents and communications between activist groups and their funders further reveals how this strategy has been implemented over the past several years, contributing to bans and other restrictions on fracking.

At a rally in Butler, Pa., a young girl was given a sign declaring a linkage between fracking and health problems. Source: StateImpact Pennsylvania

Shonkoff’s memo was prepared for the 11th Hour Project, which funds a number of prominent anti-fracking groups, including Earthworks, Food & Water Watch, Friends of the Earth, New Yorkers Against Fracking, and the Post Carbon Institute. The memo provided a blueprint for activists to target shale gas development with emotional arguments about alleged community health problems, utilizing the media to enhance their advocacy.

But Shonkoff identified a problem: there was no hard evidence to support these health claims, which hindered environmentalists’ goal of securing more regulation for the industry.

“[T]he lack of robust, causal data that links hydraulic fracturing to health has slowed the efforts of NGOs, activists, and others focused on regulatory reform and community health protection,” Shonkoff observed.

If activists wanted to succeed in suing the industry and imposing additional regulations, they would need studies and research, Shonkoff explained:

“[T]he development of a scientifically rigorous body of evidence of environmental health threats is crucial to the engagement in litigious battles, to drive regulation, and to hold the oil and gas industry accountable for their actions. Indeed, an enormous body of studies was an integral component in the struggle to bring the tobacco industry under regulation and it will likely take many authoritative studies do the same to the fracking industry.” (p. 17; emphasis added)

There was a need for “many authoritative studies” to implement this strategy. But what exactly defines an “authoritative” study? The answer, as it turned out, was whatever the anti-fracking community wanted it to be.

New York PR Strategy

In 2012, New York residents were greeted with worrying news: “Link Between Low Birth Weight and Fracking, Says New Research,” read the headline from a local newspaper. Soon after, anti-fracking activists as far away as Texas and western Canada had dutifully shared the news, creating an echo chamber that attempted to expose what appeared to be a dark side of America’s shale energy revolution. New Yorkers Against Fracking even hired a public relations firm to distribute the research and convince reporters to cover the story.

By the time a New York Times investigation revealed fatal flaws in the research, the damage was already done. Fracking opponents had successfully used the media to publicize health impacts from fracking, even as the author of the paper, a graduate student named Elaine Hill, expressed regret for going public before her work was peer-reviewed. Her regret came after a number of prominent health experts told the Times that the study was “a badly suspect piece of work,” among other criticisms, forcing Hill to rethink her decision to work with anti-fracking interests to promote her paper prematurely.

But the PR strategy worked. When New York released its health review on shale gas development, which the state used to justify a ban on fracking, Ms. Hill’s working paper was listed as part of the state’s body of evidence.

The Shonkoff memo endorsed the kind of media outreach used to promote Ms. Hill’s paper:

“[T]he effect of ‘one-off’ projects, such as a single scientific study out of a university destined for an academic journal, will fade more quickly than a study informed and engaged with by impacted communities (Robinson 2012), popularized in the media, and translated into reports and other materials for popular consumption.” (p. 16; emphasis added)

Other health claims in New York’s review were similarly suspect. One of the more prominent studies concluded there were “potentially dangerous” air emissions levels associated with hydraulic fracturing. The paper was written by researchers with close ties to anti-fracking groups, including Global Community Monitor (GCM), which invented the “bucket brigade” method of capturing air samples. Collected in buckets lined with plastic bags, these samples were presented as evidence in the paper, even though the group has admitted the bucket brigade is “not a scientific experiment.”

Worse still, the GCM paper was peer-reviewed by three individuals, all of whom oppose fracking. None of them, however, disclosed that to the publishing journal. One of the peer-reviewers was actually the co-founder of New Yorkers Against Fracking, but she omitted that from her disclosure form. She even declared “no competing interests,” while telling the journal that she thought the study was “of outstanding merit and interest in its field.”

Despite these significant conflicts of interest, the study was treated as “bona fide scientific literature,” according to Howard Zucker, New York’s health commissioner. Zucker literally held the paper up at a December 2014 press conference announcing his recommendation to ban fracking in New York.

GCM’s bucket brigade bragged several years ago in Louisiana that “its media work has resulted in more than 700 stories since 2000.” The Shonkoff memo explicitly recommended that big donors should “fund Global Community Monitor.”

‘Physicians’ Front

At the center of the anti-fracking health strategy is an Ithaca, N.Y.-based group called Physicians Scientists & Engineers for Healthy Energy. PSEHE has over two dozen staff members, directors, fellows and advisors, which include a broad spectrum of personalities, from former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials to advocates of the discredited Peak Oil theory, as well as individuals affiliated with the Post Carbon Institute.

The executive director of PSEHE, Dr. Seth Shonkoff – the author of the 2012 strategy memo – is a regular fixture in the news media on the subject of fracking and alleged health impacts. The group was founded by Dr. Anthony Ingraffea, a professor at Cornell University and prominent anti-fracking activist. His most famous study is also one of the most controversial and widely-refuted reports on methane emissions from shale gas development. The paper used data from Russian pipelines to simulate emissions in the United States, generating abnormally high emissions rates that do not reflect American operations. Numerous peer-reviewed studies have shown that his study dramatically overestimated leakage rates.

But activism is at the core of PSEHE’s activities, including the studies they publish and distribute to the press. Dr. Ingraffea has admitted that his research is a “form of advocacy,” and that he deliberately includes “advocacy-laced words and phrases in our papers.” He also suggested that his research projects begin with a conclusion already partially conceived.

“I’d be lying if I told you I went into every one of those with an entirely objective, blank opinion,” Ingraffea has said.

From left to right: Actor Mark Ruffalo, Dr. Tony Ingraffea, Sean Lennon, Yoko Ono, and Gasland filmmaker Josh Fox.

Dr. Ingraffea similarly admitted that he works with Hollywood celebrities to amplify his work, telling an audience recently that “the principal megaphone has been celebrities.”

“But the principal megaphone has been celebrities. People whose names you know better than [inaudible] celebrity follower, but Mark Ruffalo has a couple million Twitter followers. I’ve never issued a tweet in my life and never will. So, every once in a while Mark emails me or calls me and says ‘What have you got?’ And I give him 144 characters and he tweets it. He is my megaphone. Doesn’t cost me anything, doesn’t cost him anything. We don’t have anything – he doesn’t have the money, I don’t have the money. Well, he’s got more money than I do, but we can’t go on national TV at the drop of a hat, in-between segments of the national news. We don’t have that opportunity. This is unsymmetric warfare, if I could use that phrase. What the industry can do with its PR and advertising arm is infinite, compared to what you or I could do. So, Yoko Ono, Sean Lennon, Mark Ruffalo and a few others, they’re my megaphones.” (emphasis added)

Hooray for Headlines

In September 2013, a peer-reviewed study performed in collaboration with the Environmental Defense Fund found methane leakage from natural gas production was lower than previously thought, directly contradicting Dr. Ingraffea’s previous research. Within minutes of its release, however, Dr. Shonkoff and Dr. Ingraffea paid for a release on PR Newswire calling the research “fatally flawed,” while trying to contrast its results with what happens in the “real world.” The duo published the release in their capacities with PSEHE.

The release even attacked the integrity of the scientists who published the study, saying the study was “financed by [the] gas industry,” while also claiming the scientists “failed to employ basic scientific rules.” The study was published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Ralph Cicerone, then the president of the National Academy of Sciences, countered the kind of criticism that Dr. Shonkoff and Dr. Ingraffea made. The study’s authors represented “some of the very best experts around the country,” Cicerone said, adding that “it doesn’t matter who is paying these people. They’re going to give you the straight scoop.” According to his obituary in the New York Times, Cicerone was a heavy weight in the climate science community, and was called “a champion of science” by the chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Undeterred, PSEHE released a trio of studies the following April that linked methane emissions and health risks to shale gas development. Energy In Depth obtained an email that Dr. Shonkoff sent to donors and supporters of PSEHE after those studies were released, which celebrated not only the way in which PSEHE shaped media coverage, but asked for additional funds to continue influencing how the press covers shale gas.

“Three peer-reviewed articles written or co-authored by PSE staff and leadership have been released over the past 4 days and are changing energy headlines across the U.S. and the world,” Shonkoff wrote. “Your generous support today can help us to reach even more media sources and to generate and translate more critical studies.”

One of the studies suggested methane emissions from shale gas wells could be 1,000 times larger than previously thought. Shonkoff touted PSEHE’s coverage in the Huffington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Salon, among others. Another study looked at “the public health dimensions of shale and tight gas development,” which received coverage by the left-wing publication Mother Jones.

“Hooray!” Shonkoff added in his email. The focus on news coverage mirrored the strategy he laid out in his 2012 memo, when he wrote about the importance of getting anti-fracking research “popularized in the media.”

While Shonkoff was celebrating the headlines with his donors, a New York Times reporter thought something was fishy. For the PSEHE methane study, according to the Times, “much of the news coverage and commentary was greatly oversimplified.” Dr. Louis Derry, a professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at from Cornell University, told the Times that at least some of the alarming headlines “do not reflect the transient nature of the process,” adding that “it may turn out that at least some of this flux is not the result of shale gas drilling at all.”

The study area was in Greene County, Pa., the largest coal mining county in the Commonwealth. Dr. Derry noted that the methane emission signature from a nearby coal mine “is so strong that it’s not possible to resolve any contribution from the well pad.”

The study’s impact, however, was already secured. Two years later, a Google search for the study still primarily yields alarmist headlines like “Unexpected loose gas from fracking” from the Washington Post, and “Big Leaks Found in Pennsylvania Fracking Wells” from Scientific American. Nothing on the first page of results suggests any nuance, much less Dr. Derry’s criticism and the possibility that the methane may not even be originating from natural gas wells.

Once again, the media strategy had worked.

Working Backwards from Asthma

In July 2016, research from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health drew a link between shale gas development and increased asthma attacks. The study received nationwide coverage, including CNN, the Chicago Tribune, USA TODAY, and the Baltimore Sun. “Fracking wells increase rate of asthma attacks in nearby residents, study finds,” read the headline from PBS. Headlines from other outlets were similarly alarming.

Curiously though, Reuters buried in its coverage that “the study doesn’t prove fracking causes asthma or makes symptoms worse.” The researchers also quietly admitted that making any sort of causal connection “awaits further investigation.”

There is little evidence that the gap between the sensational headlines and the researchers’ findings caused the authors much grief. There were no reports of news outlets correcting their stories as a result of outreach from the researchers.

In fact, the anti-fossil fuel Post Carbon Institute, where study co-author Brian Schwartz is a fellow, even bragged about the alarmist coverage. “Schwartz quoted in UPI article on fracking links to asthma,” read the press release from PCI.

Once again, the Shonkoff memo provides interesting context on this study in particular.

The Schwartz study was years in the making. Shonkoff wrote in his memo how Dr. Schwartz had “submitted an NIH Research Project Grant Program (R01) grant application in October 2011 and will resubmit the grant in July of 2012.” But Shonkoff described the research as if Dr. Schwartz and his team had already made their conclusion:

“The team hopes to study the effect of fracking on human health in the Marcellus Shale region with asthma as the primary health outcome, using electronic health record data over the past 10 years. The team will resubmit the grant for the July 5 NIH deadline (Schwartz 2012).” (p. 12; emphasis added)

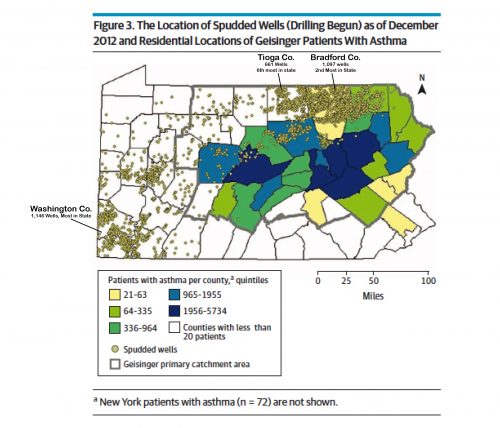

Notably, the Schwartz study looked at asthma exacerbations in Pennsylvania, but it did not include data for Washington County, which has the most shale gas wells in the entire state. Additionally, the vast majority of the more than 35,000 asthma patients included in the Schwartz study lived in areas with little to no shale gas development.

County by county map of asthma patients and shale wells in Dr. Brian Schwartz’s 2016 study. Source: Rasmussen et al. (2016)

Sound Bites and School Children

Undoubtedly, stories about potential harm to school children will catch the public’s attention. Parents want their kids to be safe, and no one wants unsafe learning environments for the next generation.

That’s why the anti-fracking movement has focused on children, schools, and playgrounds to make emotional arguments against development. A staffer for Food & Water Watch – one of the most vocal anti-fracking groups in the United States – has a training video entitled “Lobbying for Kids,” which is described as a “practical training for Kids Against Fracking on how to lobby elected officials to stop oil and gas fracking.”

Sam Schabaker with the anti-fracking group Food & Water Watch explains how children can more effectively lobby elected officials.

In 2014, ShaleTest – which is “proudly affiliated” with the anti-fracking group Earthworks – released a report called “Project Playground: Cleaner Air for Active Kids.” The group gathered air samples near “several children’s play areas in North Texas that are located in close proximity to natural gas shale development.” ShaleTest then compared the findings against state-established health thresholds.

For benzene, ShaleTest said the results were “particularly alarming” because “they exceeded the long-term ambient air limits set by the TCEQ, and benzene is a known carcinogen.” Uncritically, E&E News wrote that the benzene levels “exceed state recommendations,” and that ShaleTest’s results “could also become election fodder in Denton, where a Nov. 4 election will decide whether to ban hydraulic fracturing in the city limits.” E&E News did not disclose the group’s affiliation with Earthworks.

The State of Texas has criticized ShaleTest on multiple occasions for its dubious testing methods, which the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) called “not scientifically appropriate.” ShaleTest was comparing its short-term monitoring results against long-term exposure values, the latter of which typically require at least a year’s worth of averaged data. TCEQ’s short-term health threshold is actually five times higher than ShaleTest’s highest reading.

Additionally, when New York Health Commissioner Howard Zucker announced his recommendation for a fracking ban in his state, he cited his children as a key reason for his decision.

“Would I let my child play in a school field nearby or my family drink the water from the tap or grow their vegetables in the soil?” Zucker asked rhetorically. “After looking at the plethora of reports…my answer is no.”

According to the New York Daily News, Zucker has no children.

The Shonkoff memo suggested that incorporating children into anti-fracking advocacy strategies would create a “powerful narrative” to help promote additional regulation. At the center of that plan was a recommendation from Earthworks to focus on schools:

“As demonstrated by the findings in this report, the common denominator of many public health identification issues with the fracking process is poor regulatory infrastructure. A particularly interesting recommendation is to fund a campaign for ‘frackfree school zones’ in key states (EarthWorks 2012) because of its powerful narrative and sound-bite alignments with the tobacco-oriented ‘smoke free zone’ and the anti-narcotic slogan, ‘drug free school zone’. If this campaign leads to regulatory reform on setbacks from schools, it could also be major protection for the public health of a sensitive population.” (p. 19; emphasis added)

Dr. Shonkoff’s reference to “setbacks from schools” is also notable, as environmental interests have focused on that exact issue in pushing for restrictive local ordinances or even de facto bans on drilling.

In Texas, Earthworks is actively supporting anti-fracking legislation called the “Protect Our Children Act,” which would give cities the ability to impose uneconomic setbacks of 1,500 feet from schools. Despite the emotional branding, the Houston Chronicle says the likelihood is “slim” that the bill will ever pass.

Babies as ‘Great Visuals’

The emphasis on children in the Shonkoff memo mirrors a tip sheet that the Sierra Club prepared several years ago, which instructed people on how to make emotional arguments in support of EPA regulations targeting the energy industry. U.S. Senator Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.) referenced the document on the Senate floor as a “playbook” that environmentalists have used for “deceiving the public.”

The tip sheet, designed specifically for a public hearing on EPA’s plan to regulate carbon dioxide, recommended against focusing on hard data or scientific facts. “Don’t worry about highly technical information,” the Sierra Club advised.

Instead, the Sierra Club told speakers to “make it personal” by referencing emotional details about one’s own circumstances: “Are you a teacher, childcare provider, or coach who works with kids who have learning disabilities?”

The tip sheet also described several “great visuals” to bring to the podium to “help you tell your story,” including “family portraits” and “asthma inhalers, medicine bottles, healthcare bills, and medication for air-toxics related illnesses.”

Another bullet under the “Visuals” category recommended “holding your baby with you at the podium, or pushing them in strollers, baby car seats, baby-bjorns. Older children also welcome.”

Sierra Club staffer Mary Anne Hitt, who believes fracking “threatens communities across the nation,” holds her daughter at a pro-EPA regulation rally in May 2012. Source: Sierra Club

At the hearing where Sierra Club had encouraged people to bring their children as “great visuals,” one of the Sierra Club’s lead anti-coal staffers appeared at the podium holding her two-year-old daughter.

Follow the Money

Under the heading, “Build a Fracking Funders Network,” Dr. Shonkoff’s memo listed the major institutional funders of anti-fracking advocacy. The foundations have bankrolled many of the high-profile studies that link fracking to various health problems, though they have often escaped mention in the news stories covering those reports.

Far from being independent entities acting purely in the public interest, the foundations that fund anti-fracking advocacy are coordinating and collaborating because it “looks good for the cause,” according to Dr. Shonkoff:

“Given the large need and the small number of funders in this arena it is important to coordinate. Funding coordination increases efficiency, minimizes the duplication of efforts, increases networking possibilities, builds multi-sectoral power, and grows connectivity across the funding environment (which looks good for the cause). The funders that currently work on fracking issues relevant to public health are: the Heinz Endowments, the Park Foundation, The 11th Hour Project, the Claneil Foundation, and the Pittsburgh Foundation. Others such as the William Penn and the Colcom Foundations have expressed interest in making grants in this space. As discussed in Chapter 3, a fracking network has begun to emerge at HEFN, but could be strengthened by co-funding projects and other collaborations.” (p. 16; emphasis added)

Activist groups that are funded by one or more of these foundations have gone to great lengths to suggest the funds are not tied to any broader cause or agenda.

“Donors who support our award-winning environmental journalism do not have access to our editorial process or decision-making,” reads a declaration on InsideClimate News’ website, which has been accused of being a shadowy green PR outfit that claims to be an objective, non-profit news outlet. The Shonkoff memo identified non-profit journalism as being “useful for messaging.” The foundations that Shonkoff identified as working on “fracking issues relevant to public health” included the Park Foundation, which funds InsideClimate News.

According to a report in Philanthropy Roundtable, Dr. Robert Howarth at Cornell University – who coauthored the infamous and widely-debunked methane study with Dr. Anthony Ingraffea – said that the Park Foundation approached him in 2010 “to consider writing an academic article that would make a case that shale gas was a dangerous, polluting fuel.” Park funded the study that the researchers later published.

Howarth said it didn’t matter, because “$35,000 won’t buy my opinion.” Dr. Howarth recently joined the board of Food & Water Watch, which calls fracking “an unsafe process that harms our drinking water and health.”

Conclusion

It is unclear how many anti-fracking groups have read and deliberately incorporated the advice in the Shonkoff memo. The groups that did so have rarely – if ever – acknowledged his guidance, much less the document itself.

But what the Shonkoff memo illustrates is that many of the health accusations against fracking are part of a broader strategy that has been years in the making. Many of the high-profile studies connecting fracking to health issues were not only promoted by anti-fracking groups, but were also strategically planned to impact public opinion.

It’s also notable that Dr. Shonkoff presented his findings to the 11th Hour Project, which funds some of the most prominent anti-fracking groups in the United States, all of whom play a role in amplifying research that casts doubt on the safety of shale development.

Moreover, the memo confirms that the foundations funding anti-fracking health research are active participants in the campaign. They actively coordinate and have even developed internal networks to share ideas and research. Funding from the Park Foundation or the Colcom Foundation, for example, is often either ignored by the press or given little attention, even though the funds are being used deliberately to advance a particular political goal: to ban or restrict hydraulic fracturing.

By design, the result of this health strategy has been economically destructive restrictions on oil and natural gas development in the United States. New York’s fracking ban was influenced heavily by health studies that were written, funded, and even peer-reviewed by anti-fracking interests. Health claims have also contributed to local bans and moratoria in Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Ohio, which in turn have led to costly lawsuits for which taxpayers ultimately must pay.

This is not to say, however, that all health studies focusing on shale gas development were prepared with nefarious intent. Many scientists and university researchers have a genuine interest in addressing community concerns, and the studies they author are intended to inform local decision-making with hard data.

But the environmentalist strategy, as laid out in the Shonkoff memo, makes it harder to differentiate between credible research and studies that were motivated by a political agenda.

Lest there be any doubt about what Shonkoff was trying to do, his memo called for “coalitions that have a drive to work together in multiple areas and across multiple sectors with common goals,” including a broader attack on all fossil fuels.

“Indeed fighting coal in isolation is part of the reason that we currently have a natural gas problem,” Shonkoff wrote.